“Are there any books of or about music?” asked a member of the virtual audience towards the end of my 1 April 2021 Fireside Chat on the original St Ignatius College Library with Will Fenton of the Library Company of Philadelphia. “Probably,” I answered, based on my knowledge of the centrality of music and the arts to Jesuit education. While none of the student interns or myself had researched musical holdings in the library, our experience with the collection had shown it often aligned with nineteenth-century Jesuits interests.

As it turns out, the early Jesuits at St Ignatius College collected fewer books about music than one might expect from a Jesuit school. Anna Harwell Celenza’s excellent essay in Crossings and Dwellings: Restored Jesuits, Women Religious, American Experience (2014) reveals how Georgetown College, another Jesuit school, saw music as “an essential part of its cultural mission, and, even though the role of music in the curriculum waxed and waned during the school’s first century and a half, its symbolic power as a unifying force remained strong.” As early as 1792, the Georgetown Jesuits hired a music professor who taught vocal and instrumental music to the older students. Employment of music faculty frequently depended on the health of the college’s finances over the coming decades, but by mid-century the school offered an array of musical opportunities. Awards were given to students who excelled in music, instrumental bands and singing clubs were formed, an acoustically-sound concert space was designed, and the college bestowed the nation’s first honorary doctorate in music in 1849. Students exhibited their proficiency in instrumental and vocal performance every St Cecilia’s Day (November 22). An 1868 inventory reveals Georgetown’s library supported these initiatives through a “wide array of books on music and theater,” ranging from practical treatises on the singing of Gregorian Chant to collections of Irish songs and Latin Hymns.

Beyond the curriculum, music played a key part in religious services at churches connected with Jesuit colleges. An account in the Woodstock Letters, the internal magazine for the American Jesuit Order, of a successful eight-night men’s retreat hosted by the Cincinnati Jesuits related how each meeting began with the “singing of the Miserere by a choir of scholastics and fathers”. The final night included a “solemn benediction, Papal blessing, and Gregorian music by a choir of male voices” (WL January 1874, III:1, p. 74-75). Holy Family, the Jesuit neighborhood parish church located next door to St Ignatius College, had a “superb” organ, reputed to be at the time the largest of any such in the United States. Raising funds for the organ was a passion of Fr Cornelius Smarius, SJ (1823-1870), who passed before the instrument was played. “He did not live to hear the rich music issue from its wilderness of pipes,” a fellow Jesuit remembered; “but the first time they sent forth the tones of requiem, was at a funeral Mass for the repose of his departed spirit” (WL September 1873, II:3 p. 208).

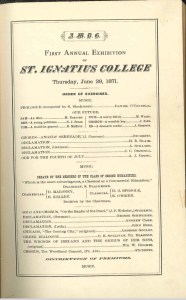

Music also featured prominently in these school’s annual end-of-the-year exhibitions. Such celebrations combined music, debates, orations, and short skits, followed by the awarding of premiums for student accomplishments in a range of classes. At St Ignatius College, some years they featured songs by popular contemporary composers as diverse as German choral conductor Franz Wilhem Abt (The Woodland Concert, 1871), Italian vocal teacher Giuseppe Concone (Angels’ Serenade, 1871), English composer Stephen Glover (What are the Wild Waves Saying?, 1872), Welsh singer John Rogers Thomas (The True Cross,1872), and American songwriter Joseph Philbrick Webster (On the Banks of the Pearl, 1871). Other years the Jesuits selected a more classical repertoire, such as Strauss’s Blue Danube (1874 exhibition), or operatic fare, as in the 1875 exhibition, which featured “Maffio Orsini, Sigora” from Donizetti’s Lucrezia Borgia (1833).

Despite the presence of music throughout the Jesuit college campus, the library at St Ignatius College had no dedicated section to books about music. The interested reader had to look closely in a few different areas of the library to find material and even then, there was not much to be found. Within the “Manufacture and Arts” segment of the Natural Philosophy section, for example, a reader could find John Weeks Moore’s Complete Encyclopaedia of Music, Elementary, Technical, Historical, Biographical, Vocal, and Instrumental (Boston, 1854) and Louis Girod’s De la Musique Religieuse (Namur, 1855), the latter a history of Catholic sacred music. Yet “Manufacture and Arts” served as something of a catch-all for the creative arts, including books on architecture, armor, art history, drawing, engraving, furniture, photography, printing, technical education, and textiles. The Natural Philosophy section, a subset of the Philosophy Division (one of the six divisions that organize the catalogue), also included all the library’s books about mathematics, science, and “Miscellanea.” Silas Casey’s Infantry Tactics, for the Instruction, Exercise, and Manœuvres of the Soldier, a Company, Line of Skirmishers, Battalion, Brigade, or Corps d’Armée (New York, 1863) was among the Miscellanea. Casey’s manual explains how music can be deployed in battle formations, and that is a small part of a much larger three-volume set. The Miscellanea section really is a catch-all, including books on subjects as diverse as book-keeping, cooking, etiquette, magic, penmanship, stenography, and even two editions of the Index Librorum Prohibitorum, the Catholic Church’s banned book list. (This might also suggest how little stock the St. Ignatius Jesuits put by the Index, as argued in earlier posts by Gustav Roman and Roman Krasnitsky.)

A handful of books about secular music could be found scattered throughout the collection. Works related to musicians, such as the collected writings of German composer Richard Wagner (New York, 1875) and a biography of Carl Theodor Körner (London, 1845) whose poems were put to music by Carl Maria von Webster and Franz Schubert, can be found in subsections in Literature and History. There are also collections of ballads in the Poetry section – Charles Duffy’s The Ballad Poetry of Ireland (1845), Charles Rogers’ The Scottish Minstrel (1870), and Mary Anne McMullen Ford’s Snatches of Song (1874) – although their presentation is without musical accompaniment. Some periodicals, such as The Rambler, a Catholic serial published in London, included music among their diverse content. Few of these books survive today in the Loyola University Libraries, so there is no way of knowing if the original books might have provided any evidence of how they came into the collection.

While information about secular music appears in scattered locations throughout the library, books the Jesuits collected about sacred music are more centralized.

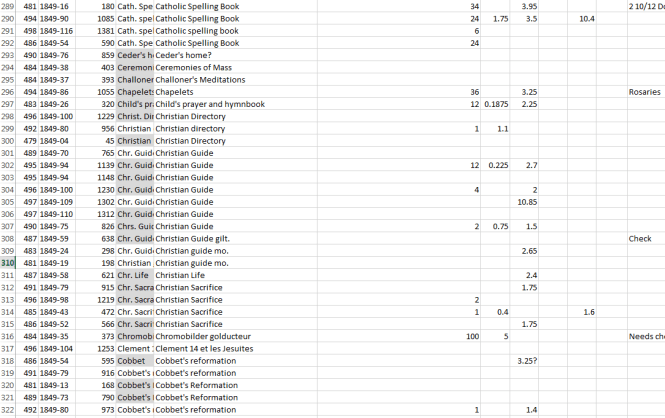

Catholic music is to be found almost exclusively in the Liturgy section of the Theology division. As the title of the section suggests, here readers could find information about the rituals of public worship performed by the community of the Catholic faithful. The liturgy of the Catholic Church evolved over the centuries, consolidating in the Western church around the Roman Rite as a result of standardization provided by the advent of the printing press and the promulgation of decrees in the Council of Trent (1545-1563). In the nineteenth century, the Roman Rite was performed in Latin and noted for its formality. Multiple publications developed to support this liturgy, the most central being the Missale Romanum (Roman Missal), which by the 1570s contains the text and rubrics (instructions for the priest) for the celebration of the Tridentine Mass. Nine different missals could be found in this section of the library. The earliest dates from 1647 and has an inscription which indicates it was plucked from a corpse on a Civil War battlefield before it entered the St Ignatius Collection. The remainder, none of which survive, date to the mid-nineteenth century, and were published in the United States, Ireland, and Belgium.

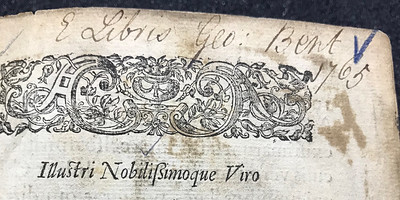

Musical accompaniment for the Mass developed over time, with specific books emerging to support different facets of the liturgy. The St Ignatius Jesuits often collected these works in multiple editions. For example, the library had three copies of the Graduale Romanum (Roman Gradual), which collects all the musical elements (largely chants and psalms) of the Mass of the Roman Rite. Seven copies of the Rituale Romanum (Roman Ritual), which contains all services performed by a priest or deacon not in the Roman Missal or Roman Breviary, are to be found in the collection. No copies of the Graduale Romanum appear to survive, but three copies of the Rituale Romanum do. Two copies of an 1845 edition published in Mechlen, Belgium, were given by the Jesuits at St Louis, a recurring pattern in the Missouri Province, many of whom were originally from Belgium and likely preferred Belgian imprints. An elaborate 1735 Antwerp edition also survives with an 1849 gift inscription to James P Donelan, then Pastor of St Matthew’s Church, Washington, DC, from “his excellency Sr. A Calderon de la Barea, minister Plenipotentiary and Envoy Extraordinary of Spain.”

The Catholic Church adopted its liturgy to be performed from dawn to dusk, often with some form of musical accompaniment. An Extracts for the Roman Gradual (New York, 1869) provided liturgy and music for morning prayers while the Manuale Cantorum was used in the Divine Office. The Jesuits had two 1810 Belgian and an 1869 Cincinnati edition of the Manuale. At the end of the day, books of Vespers (two French – 1824, 1844 – and one Belgian, 1854) provided the chants and songs for the evening prayer service which takes place as dusk begins to fall. Only an 1810 edition of the Manuale Cantorum from this lot survives. It, too, was given by the Vice Province as part of the starter collection and bears the inscription and what may well be a pencil sketch of the previous owner in Flanders.

The final musical work in this section is A Choir Manual published in Dublin in 1844. This work was part of a mid-century revival of Gregorian Chants, “of the noble old music of the Church”. One reviewer for The Dublin Review (September 1846) placed this rethinking of sacred music among the English, Irish, and Belgian branches of the Catholic Church in response to increasing use of hired (“especially female”) singers, solo pieces, and more secular music forms – “souvenirs of the ballet; variation upon quadrilles, polkas, or ‘galopes’’. The revival had come none too soon, according to the reviewer. “[T]he ordinary Church-music of Belgium three or four years ago certainly appeared, even to those who were not inclined to be censorious, to have reached the ultimate point of levity and secularity.” All male choirs proved the antidote, the reviewer continued, engaged in singing simple plain chant. Not only did A Choir Manual include a “Grammar of Music,” it also had a Gradual and a Vesperal. While the choir manual did not extend “literally to all the days of the year” it left “comparatively little to be supplied.” This was a “High Mass at certain places looked upon as a kind of Sunday opera” (p. 202-205).

Mindful of the crowded spiritual marketplace, Jesuits also collected materials produced by their Protestant competitors, several of which included music. These materials were also shelved in the Theology division, but in the tenth and final section, which served as something of a catch-all for religious materials which did not fall neatly elsewhere. That section, ostensibly for Ascetical Theology or Mysticism, also included subsections for heterodox works and prayerbooks. In the last could be found several sources of Protestant material. These include hymn books issued by the Protestant Episcopal (1841), Methodist (undated), Presbyterian (1843, 1855), and Swedenborgian (1848) churches. None of these books survive in Loyola University Libraries today, making it difficult to know from where they came.

Just because the St Ignatius College Library did not have many music books, however, does not mean such books could not be found in other corners of campus. An 1865 Baltimore edition of Ceremonial for the use of the Catholic churches in the United States of America bears an embossed stamp for Holy Family Church, a reminder that the Jesuit parish church also had its own collection of books and might have been a more significant repository for books of sacred music.

Further investigation is required to know if St Ignatius is representative or anomalous for the paucity of books about music in its collections. Georgetown certainly had a more robust collection, as has already been stated, but it had an eighty-year head start on St Ignatius, with the luxury of time to build out its curriculum. For other Jesuit colleges founded in growing US cities following the American Civil War, collecting books about music might have been seen as less of a priority than books needed directly for the curriculum.

Further Reading:

To learn more about the place of music at Georgetown College, see Anna Harwell Celenza, “A Jesuit University in the New World: Music’s Cultural Mission at Georgetown University (1789-1930” in Kyle Roberts and Stephen Schloesser, Crossing and Dwelling: Restored Jesuits, Women Religious, American Experience, 1814-2014 (Brill, 2017), 380-405.

The Woodstock Letters (abbreviated WL above) are a rich source for exploring the North American Jesuit community in the last quarter of the nineteenth century. They have been digitized and made fully-searchable as part of Boston College’s Jesuit Online Library.

The Course Catalogues for St. Ignatius College provide annual snapshots of the curriculum, students, and exhibitions at the school. They have been digitized by the Loyola University Archives and Special Collections.

Special thanks to Ashley Howdeshell and Kathy Young of the Loyola University Archives and Special Collections for their help with some of the surviving books referenced in this essay. Thanks, as well, to Will Fenton, formerly of the Library Company of Philadelphia, for the opportunity to give the talk which generated the questions answered here.