Erik Berner returns with his next installment on secular legislation books in the original St. Ignatius College library collection. In this post he looks at British books in the collection, including some early and rare copies of the Magna Carta.

Magna Carta (London: Robert Redman,1529)

Magna Carta (London: Thomas Wight,1602)

John Gifford, The English Lawyer (London: 1828)

Jean Louis de Lolme, The Constitution of England (London: 1871)

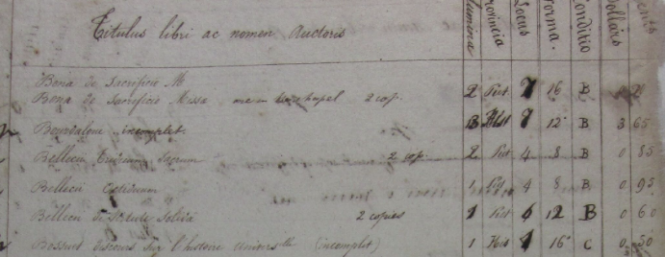

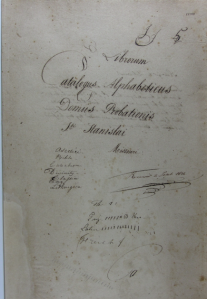

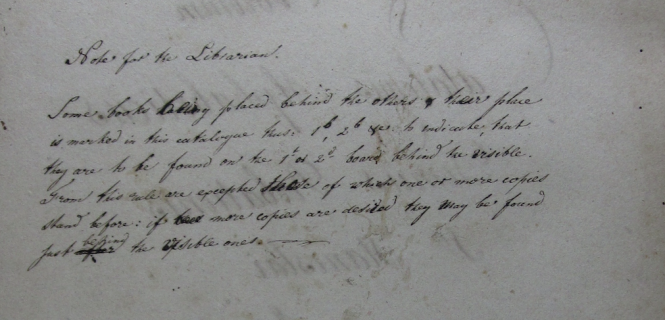

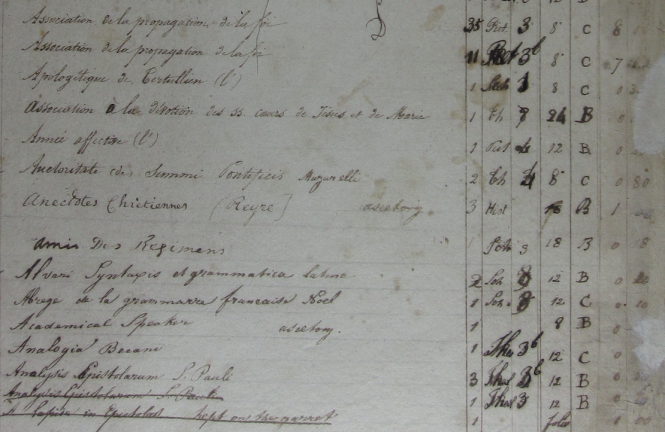

One of the ways in which I have grouped the books listed in the Secular Legislation section of the original library catalog is by region. I have separated them into three applicable regions: British, Continental (Europe), and American (further subdivided into the colonial and national periods). The British grouping contains four works. Two of these works, copies of the Magna Carta from 1539 and 1602 respectively, are the oldest items in the catalog, and are both still held by the Loyola libraries. The other two — The English Lawyer by John Gifford, and The Constitution of England by Jean-Louis de Lolme — are no longer extant in Loyola’s collections. A digital copy is available of an edition of Gifford’s book printed five years earlier (1823), but with similar publishing details. Researching the de Lolme book touched off an interesting saga. The original library catalog lists an 1871 edition, but we have reason to believe that it might have actually been a 1781 edition, a possibility that will be discussed in detail later in this post.

A charter granted to the rebellious noble barons in 1215 by the unpopular King John, the Magna Carta is often held up as a precursor to the Constitution of the United States and as a great originator of individual rights law for the people. This is not entirely accurate. In actuality, much as the Constitution of the United States was originally intended for a bourgeois citizenry (read: white, male, property owners), the Magna Carta, when issued by King John, was never actually intended to grant habeas corpus to John Commonman in Common Village, Commonshire, so to speak. It was intended to create a balance between the potentially despotic authority of the King and the rights that men of property, nobility, and privilege felt that they should have and exert against said authority. This, much as the general governing agreement between King William of Orange and the Parliament upon his installation on the throne, was intended to preserve the English Monarchy from rebellion, while giving those with money and title some power (and avoid such Cromwellian catastrophe as occurred in England in the century before the ascendancy of William).

Titles page of the 1529 Magna Carta, still in Loyola’s collections today.

Both copies of the Magna Carta listed in the catalog are still extant in Loyola Special Collections, in octavos of contrasting condition. The older, at first glance, seems in rough state. The spine is ripped and cracking, and some pages are just barely holding to it. Nevertheless, the pages themselves, and the print, are gorgeous and legible, at least in the sense of their appearance. Legibility in regards to language is an entirely different story. Though the first copy is specifically titled The Magna Carta in French, it is, in fact, largely in abbreviated Latin. (This is, according to the Smithsonian Institute, how an “original” copy would have been written: charters were transcribed in abbreviated Latin after the contents of the Magna Carta were agreed upon to facilitate faster delivery to the corners of the Kingdom). It seems too large to be just the text of the Magna Carta itself, and though I cannot read the Latin, and struggled with some of the Old French, I suspect that much of the contents are either texts pertaining to the many re-issuances by subsequent kings, or else other statutes entirely. Further research in Special Collections will be necessary to conclude this, as this book was very difficult to delve into, due to its condition. It was printed in 1529 in London by a publisher named Robert Redman. He, it seems, was the second “King’s Printer”. After the creation of the printing press, this became a position first held by Richard Pynson, and subsequently taken over by Redman under Henry VIII. The lack of any explanatory sections, particularly any in the English language, in the book, and the fact that the printer was royally affiliated, suggest to me that this was printed for legal, or personal knowledge use, of somebody in the Courts. How and why Loyola came to own it is a very interesting question.

Title page of the 1602 Magna Carta in Loyola’s collections today.

The second copy of the Magna Carta is in much better condition, though it may have been rebound at a later point. The binding, specifically, is one of the most interesting things about it, which I will get to in a moment. First, one must discuss the contents. The publisher of this book, Thomas Wight, is highly relevant to my project. He is known for being “one of the first publishers of English Law books,” according to Wikipedia. He lays out that purpose in no uncertain terms in his note “To the Reader” at the beginning of his edition of the Magna Carta. He explains that he has decided to compile both the Magna Carta, as well as other relevant English legal statutes into an edition “to bee had, perfect and readie, not onely by all Studentes of the law for their priuate Studies, readings, ootes, bolts, cafes, and other exercise, but also by the practice of the same for their dayly affaires and causes.” No guesswork is needed about the purpose of this book: printed in 1602, it was intended for personal reference of noblemen that learned law in the classic “Inns of Court” manner in the 17th century, in which law students attended court proceedings and were expected to take in the happenings and “learn independently” rather than taking on formal academic coursework for the law (a development that would not arise until later, see my previous post). He seemingly did not wish to change a single word of any of the statutes, as they alternate between Latin and Norman French (which would, at various times, have been the languages of use for laws by the Court in England). This also indicates that he simply put them down as is, creating a common law amalgamation of English precedents to be referred to by the law student. The age of this copy and how Loyola acquired it makes it of particular interest, but the binding also adds some mystery. Stamped on the leatherbound cover, on both the front and back is a golden initial: RB. Who was RB? For conjecture on this, as well as fascinating information on the publishing context of these charters, see Michael Albani’s post on the topic on the JLPP blog.

Title page of a copy of Gifford’s English Lawyer from 1823, five years earlier than Loyola’s original copy.

Gifford’s The English Lawyer, as its subtitle suggests, falls into the “every man his own lawyer” category of self-help law books we have discussed, which were popular around the time of the book’s creation. It was originally published in 1820 and St Ignatius College had an edition from 1828 according to the original library catalog. The nature and contents of Loyola’s copy, as gleaned from an 1823 online edition, would indicate that this was not necessarily the type of book that would have been used in an apprenticeship or Inns of Court law program (though due to the rather unstructured nature of pre-professionalized law schooling, any book that a student found useful could obviously have been referenced). Instead, this seems to be intended for the “common gentleman” to use for personal reference when partaking in the responsibilities of running a nineteenth-century household.

As stated, the online edition found was not the same one originally owned by the Jesuits. Nevertheless, being printed only five years earlier, the book, I suspect, is not substantially different and that the basic themes and contents are the same. The book focused mostly on the types of things that a gentleman would need to know to go about his daily duties and responsibilities. The book gives a thorough presentation and explication of all manner of English property, tax, inheritance, and family law. These are topics that any noble or bourgeois citizen of the time would be expected to at least be passingly familiar with, not necessarily things that would be confined to the realm of those studying to be lawyers, reinforcing my previous assertion that this book was most likely not intended for law students. It is hard, obviously, to come up with too much solid information about the physical edition that the Jesuits owned. An attempt at conjecture was made, but not even the name of the publisher remains. Some deeper research will be necessary to come up with any concrete ideas about why the Jesuits would have acquired this book, or from where.

An earlier (1853) edition of de Lolme’s Constitution of England.

The last of the UK books, and the second of the missing ones, is an edition of Jean-Louise de Lolme’s The Constitution of England. Jean-Louise de Lolme was, like many of the greatest legal commentators (think de Tocqueville), not originally from the country about which he wrote. Born in Geneva, de Lolme studied for the bar (presumably in the inns of court fashion described above) and originally wrote theoretical treatises. One of these in particular, about the nature of the rights of human beings (An Examination of the Three Parts of Rights) angered the authorities in Geneva enough that de Lolme went into exile in England. From here, he was able to take an outsider’s perspective of the English legal system, a system which, through its maintenance of balance between different classes, impressed him greatly. He decided to write about it in a proscriptive manner in the French language, presumably with the hopes of influencing French speaking people on the continent to strive for a system more like Britain’s. The book was first published in French in 1771. An English translation was made in 1775 in London by T. Spilsbury. It went through another English-language edition two years later before being printed by its most familiar English language publisher, John Murray, who reprinted it multiple times in subsequent years.

De Lolme’s book belongs to the category of legal commentary more than anything else. The book is not a law book in the sense that it presents statutes or precedents. Rather de Lolme analyzes the English system of government, constitution, and, particularly, its “unwritten constitution” (what we would call the body of common law dictating the precedents the English followed). Though critical of certain aspects of the English system (particularly the feeling that the Parliament exerted too much influence over other branches of government), de Lolme, ultimately, holds the English model of balancing what he terms “the one, the few, and the many” or “monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy” to create what he feels is the most perfect of all the current systems. He gives his own prescriptions of how this balance might be improved and his suggestions on how its analysis could benefit the rest of the world. Indeed, at least some people in the rest of the world listened, though not perhaps the ones he had hoped would. Originally written in French, the cautious moderation of de Lolme’s politics, in the end, would not win out of the “direct democracy” ideals of his chief intellectual rival, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, when it came to political influences on the French Revolution. Some English were listening, however, particularly those on the other side of the Atlantic wishing to throw off the yoke of British monarchy. Many of the founding fathers of the United States cited de Lolme’s work as influential, and, indeed, one can see the debt the US Constitution owes to de Lolme’s idealized explication of the English one.

Again, it is hard to know why or from where the Jesuits may have acquired their copy of de Lolme’s work. It appears to have been very popular and required for any collection on politics. The original library catalog lists and 1871 edition, but the library’s copy does not exist and no digital surrogates of (or, indeed, publishing information about) an 1871 edition can be found online. On the one hand, there is an 1870 edition published by Murray in London and this might be a reprint of that. On the other hand, there might have been an error in transcribing the year by the librarian who created the catalog. It might have been an edition published in 1781 (a potential matter of simply switching two numbers by mistake). Both were published by the Murray publishing house, which still exists. It was founded in the eighteenth century by John Murray I, but it was under his son in the nineteenth century that it became, to quote Wikipedia, “one of the most important and influential [publishing houses] in Britain.” Whether given as a gift to the Jesuit collection or sought out specifically for purchase, this book is not a surprising work in the original law collection

In fact, if one looks at the legal books the Jesuits did not have (as well as the fact that they seemed uninterested in founding a “law school” when compiling their library), one begins to wonder if some of these books might have simply been collected in an ad hoc manner. Though some of these UK law texts are certainly considered essential, perhaps the most essential (certainly one of the most famous and oft-cited) English legal text of all is missing; William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England. Throughout my research, both on the theoretical works that influenced the founding fathers, as well as the books commonly used in a self-teaching or inns of court style legal education, Blackstone’s Commentaries, seem to appear every time. Though the Jesuits may have specifically sought out copies of the Magna Carta or de Lolme, by leaving Blackstone out, it seems unlikely that there was a conscious effort being made to collect the canon of English legal texts.