This summer intern María Palacio, a candidate in Loyola’s Master’s in Digital Humanities Program has been studying the earliest surviving library catalog from the Jesuit Seminary in Florissant, Missouri. This catalog has recently been conserved and made accessible to researchers. Here Maria shares some important insights gained from transcribing the catalog.

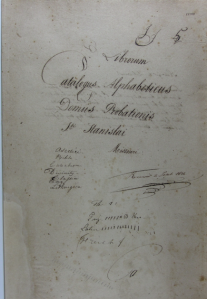

Catalog front cover.

Collection of Jesuit Archives, Central United States

Last year, thanks to a grant from Loyola’s Hank Center for the Catholic Intellectual Heritage, the fragile Catalogus Librorum Alphabeticus Domus Probationis St. Stanislai (Alphabetical Catalog of the Library at the St. Stanislaus House of Studies), was conserved and made accessible to researchers. This 65-page manuscript, begun in 1836, contains the catalog, or more precisely a series of catalogs, for the library of the Jesuit Seminary at Florissant, Missouri. When it was first established in 1823, St. Stanislaus was populated by seven Belgian novices, but it rapidly grew into one of the main centers of the Society of Jesus in the Midwestern United States over the 19th century. By 1870, the Missouri Province Jesuits, who had their origins in the once small Florissant Seminary, founded St. Ignatius College in Chicago. By 1878, St. Ignatius College’s library held approximately 5100 titles, around 6 times more titles than Florissant’s library forty years earlier. Although the Catalogus Librorum is considerably smaller than the original catalog of St. Ignatius, it is hoped that, by studying this earlier catalog, and looking for overlaps in both collections, we can better understand the history of Loyola University’s original library.

However, before we could start comparing both collections, I needed to transcribe the Florissant catalog. Given the fact that the catalog appears to have been written by more than one person, and that some of the pages are written with different ink types or even faded by humidity, this document cannot be read and transcribed by only looking at it once. Therefore, I decided to divide the transcribing process into three stages. In the first stage, which I recently finished, I tried to read and transcribe as much as I could without stopping to think a lot about the fragments that I could not read or that confused me. Instead, I marked all those cases to revisit in a second stage when I have a greater understanding of the documents and more familiarity with the different handwriting styles. Finally, in the third stage, in which I expect to have an almost definitive transcription, I will encode the text in an XML format. This encoding will allow for the better digital preservation of the transcription, and to markup different characteristics of the text: the deletions, the changes in handwriting, the type of ink, the languages, etc.

While it is too soon to compare this catalog with Loyola’s first catalog, I have been able to study this document itself, analyzing its fragments and particularities, and ask a series of questions about book circulation and organization in this Jesuit library in Missouri. By transcribing the catalog I realized that this document is actually composed of several fragments: a “Note for the librarian”, a small Index, a map of the library, a rudimentary borrowing ledger, the Alphabetical Catalog, and a second catalog (the Subject Catalog) created in a different time and by a different person.

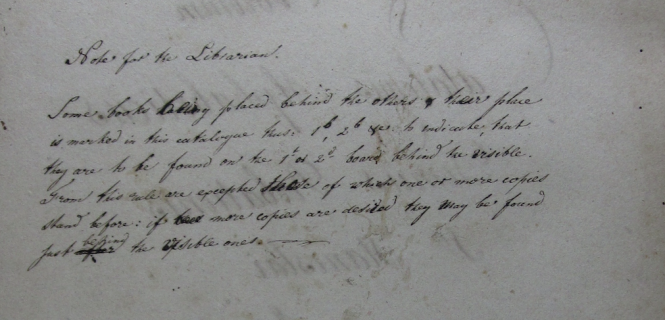

“Note for the Librarian.”

Collection of Jesuit Archives, Central United States

The “Note for the Librarian” is a short text to help the librarian understand some confusing aspects of the Alphabetical Catalog. We can establish that the “Note” is related to the Alphabetical catalog for two main reasons. First, both are written with the same handwriting and ink type, which could mean that the note was written by the same person. Second, the Alphabetical Catalog employs 7 categories to catalog the books, including Provincia, which classifies the titles by topic, and Locus which designates where the titles must be located in the library. These two categories only exist in the Alphabetical Catalog and are indirectly mentioned in the “Note.” For instance, the “Note” explains how the Locus category works: “Some books being placed behind the others, their place is marked in this catalog thus: 1b, 2b etc to indicate that they are to be found on the 1[s]t or 2[n]d board behind the visible…” By reading this note we can establish that the number in Locus determines the board in which a book was placed. Sometimes, probably for space reasons, a book had to be placed behind other books and it was not visible to the librarian. To solve this problem, the books placed behind are marked with a “b” next to their Locus number in the Alphabetical Catalog. That way, the librarian could find a book in a respective board even if it was not visible. Moreover, in the present, this piece of information can help us to partially understand Florissant’s library organization and limitations. For instance, in the Alphabetical Catalog there is a total of 46 items with this kind of Locus: 23 of books belonging to the Theology Provincia, 19 to the Scholastica, 2 to the History and 2 to Piety. More interestingly, the Provincia and Locus of almost half of these items was modified over the course of time, resulting in the need of the “b” designation to be able to fit them in a different board. This fact could lead to the conclusion that organization of the library was parallel to the creation of the Alphabetical Catalog, and it gave enough space for most of the books in each Locus and Provincia to fit well in their designated boards. However, when the classification of some items changed some space problems appeared resulting in the need to use the “b” designation more often.

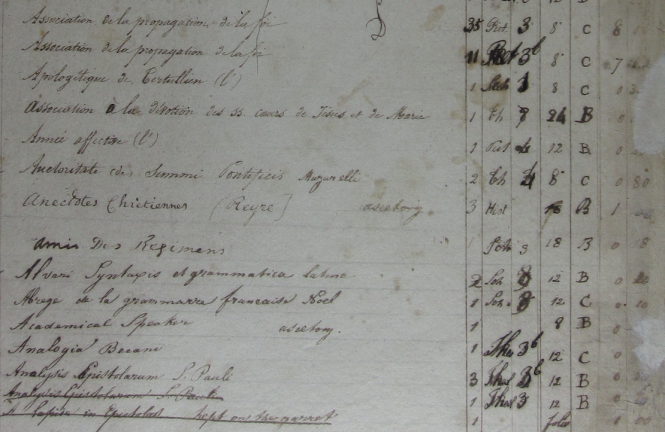

Alphabetical Catalog illustrating items marked with a “b” next to their Locus number.

Collection of Jesuit Archives, Central United States

I expected that the Index and the map would help me to better picture this library. However, apart from the fact that they appear to be written with the same handwriting, there is not a clear relationship between the Alphabetical Catalog and these segments of the document. We can be certain that the Index and the map are directly related because the categories listed in the first are then explicitly mentioned in the second. Yet, most of the categories mentioned in the Index and the map are not mentioned in the Alphabetical Catalog. While in the map, books appear to be organized in sections named as letters from A to M, in the Alphabetical Catalog books appear to be organized in the library by its Locus number. All these facts make it hard to draw a relationship between the first segments of the document, and the Alphabetical Catalog. Perhaps, since they are both written in pencil, the map and the Index belonged to an earlier or later cataloguing project.

Map of the St. Stanislaus Library.

Collection of Jesuit Archives, Central United States

Once I transcribed the Alphabetical Catalog, I realized that it was an intriguing document. The fact that is written in cursive and organized into tables, points out it was conceived to be an official catalog, and not just a temporary list of books and where to find them. There is an effort of classifying the books alphabetically by author (or barring that, title) and by topic (using the Provincia category), as well as an attempt to keep record of the location, format, physical condition, and price of the books held by the library.

However, in this document we can also find traces of usage like annotations, marks, and deletions, made with different ink types and sometimes with a different handwriting. For instance, the category Provincia, in which books and documents are classified by its topic (theology, piety, history, etc.), appears to be a continuous source of hesitation, especially when dealing with titles directly related with the Society of Jesus. Apparently, when the catalog was created all of the books related with the Society of Jesus, or written by one of its members, were listed under the Provincia IHS, the christogram used as the symbol for the Society of Jesus. However, at some point, someone, maybe a different librarian, decided to eliminate IHS as a classificatory topic and reorganize all the titles that appeared under that Provincia under other classifications. There were 47 entries of the catalog classified as IHS and, since the classification in Provincia affects the one in Locus, its elimination must have had implied a big change on the library’s organization.

Changes in Provincia in the Alphabetical Catalog.

Collection of Jesuit Archives, Central United States

Another trace of usage, that shows how this collection and the library’s organization changed over the course of time are the series of deletions and annotations that appear on the catalog. Often items are crossed out. This implies that those items stopped being part of the collection of the library. Since there is not a date accompanying the deletion, we cannot know when items stopped being part of the collection. However, sometimes, the crossed out items have a note next to them specifying that they were given away and to whom. This fact reveals to us that this collection circulated outside the Seminary. Is it possible then that some of the books of the collection ended up being part of Loyola’s first library? At this point, we cannot answer many of these questions. However, we can be certain that the library and its catalog were not static entities, and that they were constantly modified by human interactions.

Subject Catalog.

Collection of Jesuit Archives, Central United States

Around ten percent of the Alphabetical Catalog is currently crossed out. That made me think that, at some point, there appeared the need to rewrite and actualize the catalog. That could answer why the segment of the Alphabetical Catalog is followed by another catalog clearly written by another person and in a different time. The second catalog, or Subject Catalog, is considerably shorter and has a very different cataloguing approach, but it is very likely that it addressed the same collection than the Alphabetical Catalog, because there is an overlap of more than ninety percent of the titles between the catalogs. The main difference between the catalogs is that the Subject Catalog is not organized alphabetically, but in chapters by subject: the Sacred Scriptures (Bibles and the books or texts that analyze them) and Ecclesiastical history (texts about the expansion of Christianity, Catholic history, Jesuit history, etc).

Index.

Collection of Jesuit Archives, Central United States

This catalog seems to leave out all the titles that are not directly related with the Christian faith, and that were part of the collection of the Library in Florissant like dictionaries, grammar books, books about history and medicine, literature classics, etc. One possible explanation for the missing items in this catalogue is that it was never completed. However, this hypothesis seems unlikely if we take into account that the Subject Catalog has numerous traces of usage like deletions and posterior annotations. A more plausible explanation could be that some pages of this Subject Catalog are lost. We already know that the manuscript we have our hands is not complete because the section of the titles starting with the letter “C” is missing from the Alphabetical Catalog. Therefore it is not unlikely that some pages from the Subject Catalog are missing too. Furthermore, the Index and the map of the library could actually be related to the Subject Catalog and support the idea that some pages of this catalog are lost. The Index is not divided in chapters, but it is clearly divided in sections that could represent chapters. The first section lists topics like Scripture, Canon, Philosophy and Controversy which are also the topics of the books listed in the first chapter of the Subject Catalog. Moreover, the second and third sections of the Index, which lists topics such as Sermons, and Lives of the Saints also correspond with the titles listed in Chapters 2 and 3 of the Subject Catalog. The Index has four more sections that list topics like Literature, Classics, and Languages, but, since the Subject Catalog we have ends in Chapter 3, we cannot confirm if there were parallels between the rest of the Index and the possible missing pages of the Subject Catalog.

Since the Index seemed to be related to the Subject Catalog, and the map of the library is certainly related to the Index, I tried to find a relationship between the map and the Subject Catalog. However, apart from the fact that in both documents books seem to be organized in the library by letters, I could not find a clear relationship between them. While in the map books are organized in sections from A to M, in the Subject Catalog we can find books with Littteras like “O” and “S”, which are not included in the map. Moreover, in the map, letter sections are organized by topics (for instance, the books placed in the “G” section are related to English, French, and German languages), but this topics do not correspond with the topics of the books under the Littera “G” in the Subject Catalog , where we can find titles like Concordantia Bibliorum and Notitia ecclesiastica per Cabassutium. Therefore, we cannot establish a clear relationship between the Index and map and the Subject Catalog and we can not use the information in these pages to confirm the incompleteness of the Subject Catalog.

Even if the Subject Catalog is incomplete, it can still be an useful complement to the study of the Florissant’s collection, because it gives information that the Alphabetical Catalog omits. Since it is already organized by topics, the Subject Catalog eliminates the Provincia category. It also replaces the Locus category for a category called Littera (which uses letters instead of numbers to determine the placement or a book within the library) and records the year of publication, place of origin, format, and number of volumes. This latter information is very useful from a History of the Book perspective, because it allows us to better understand the origin of the items. Moreover, the introduction of the year category allows us to determine the probable date of creation of the Subject Catalog. For instance, we can establish that it must have been written at least ten years after the Alphabetical Catalog, because it contains items from years after 1836. With the information on the catalog we can also estimate that it was created around the year 1846, because there are no books from any year after 1846.

This fact could lead us to conclude that, after 10 years of usage, the Alphabetical Catalog was replaced by the Subject Catalog. But why? I already mentioned that around 10% of the Alphabetical Catalog is crossed out, and that in the Subject Catalog we can find titles that do not appear in the Alphabetical Catalog. However, are this changes enough to create a new catalog with a very different approach to the collection? Why did they did not create a new copy of the Alphabetical Catalog instead of a brand new type catalog that implied a whole reorganization of the collection? And, moreover, can we be certain that the Alphabetical Catalog was completely replaced by the Subject Catalog?

Borrowing list from 1852.

Collection of Jesuit Archives, Central United States

Previously I mentioned there is a segment of the Catalogus Librorum composed by a series of informal lists of books lent from the library. This pages could be considered a rudimentary borrowing ledger. I say rudimentary because the 11 pages that contain lists of books lent from the library do not have the same organization system or contain the same kind of information: some of them just contain a segment of the title that was borrowed followed by a name, while others are more organized tables that also contain the date in which the title was lent. However, most of this pages appear to be written by the same person who wrote the Alphabetical Catalog, which is odd if we take into account that the date of February 1852 appears in one of them. Moreover, in that same list we can find books that do not appear in the pages we have of the Subject Catalog like a Latin Grammar and a book by Virgil. Could this list help us prove that some pages of the Subject Catalog are lost? Or, could this mean that the Alphabetical Catalog, which appears to be written by the same person that the lists of the borrowing ledger, was still used by 1852? Was the author of the Alphabetical Catalog the librarian of the Florissant collection and, for that reason, his handwriting appears in documents from 1852 when the Alphabetical Catalog had been replaced? We can not answer any of these questions with total certainty, but at least we can be sure that the Catalogus Librorum Alphabeticus Domus Probationis St. Stanislai is an intriguing document that will not only allow us to compare the collections of the library in Florissant with Loyola’s first library, but also to study issues of cataloguing practices and book circulation in other Jesuit libraries.