This post reflects on the JLPP team’s work on the 1840s book trade ledger from the Missouri Province this semester. It pulls liberally from intern Bianca Barcenas’s reflections on the process in her internship blog Mapping Catholics with the Jesuit Libraries Provenance Project.

This past fall semester, three members of the JLPP team – junior Bianca Barcenas, Master’s student Dan Snow, and Prof. Kyle Roberts – turned their attention to an in-depth study of the purchases in the book trade ledger maintained by the Jesuits in St. Louis between 1842 and 1849. The original ledger is in the collections of the archives of St. Louis University, but the JLPP team was able to work with a high-quality scan of the rich document.

Dan Snow and Brendan Courtois (and fellow Ramonat Scholar Andrew Kelly) in front of the poster on their work analyzing the book trade ledger.

Both Dan and Bianca had worked on the JLPP before. Dan researched some of the more interesting vendors recorded in the ledger’s “Bill Book” section last academic year and worked with Brendan Courtois on a big picture analysis of the ledger as a financial document. Bianca spent the summer detecting the contours of Mississippi and Missouri Valley Catholicism over time through a comparative study of statistical data in the 1841 and 1851 issues of the Metropolitan Catholic Almanac (MCA). As her post from August revealed, the center of Midwestern Catholicism began to shift over the 1840s from St. Louis to Chicago and Milwaukee, as the number of parishes rapidly expanded and three new dioceses came into being. Bianca’s summer research set the stage for a formal internship in the fall semester while Dan contributed the free time he had between graduate seminars.

The semester began with each team member rolling up her or his sleeves and transcribing several months or one year of purchases from the ledger. There are over 375 pages of transactions, so it would have been impossible for the three to try to do them all in a semester’s time. Bianca had the largest data set with January to December 1846, Dan worked on May to September 1849 (the last transactions in the ledger) and Prof. Roberts explored May 1842 to April 1843 (the first transactions). In order to understand the information recorded, it first had to be transcribed and organized. This meant making an Excel spreadsheet that recorded aspects of each transaction related to the consumer: the page on which it is listed; the day, month, and year of the purchase; the prefix and last name of the purchaser; and finally any notes about the transaction. (Later in the semester the team began to add information about what each person or institution purchased.)

As her spreadsheet eventually grew to 380 transactions, Bianca found that her summertime work on the 1841 MCA offered a handy resource for making sense of nineteenth-century handwriting. Even as this early stage, names familiar from the MCA five years earlier appeared. Common names, however, made it difficult to discern whether the listed was Fr. Martins of St. Louis, Vincennes, or New Orleans.

With a preliminary spreadsheet of transactions in hand, the third, fourth, and fifth weeks of the semester were spent determining how many unique purchasers were represented. For example, 124 different clergy and laity made Bianca’s 380 transactions. Variant spellings and abbreviations of names added another layer of complexity. Was Sister Olympia the same as Sister Olimpia? Was Mr. Coppes also Mr. Copes?

Identifying clergy was made easier by the rich listings in the MCA and, for Jesuits, the Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu, both available digitally. (There are some gaps in the online holdings of the MCA, but Loyola’s Special Collections has a complete run for the decade.) The laity, however, proved a greater challenge. Most were difficult to identify with any degree of certainty. By the end of this phase of the project, team members decided to swap their spreadsheets to see if they could identify people that the others had missed. Each also selected a certain segment of consumers across the period – Bianca looking at institutions and women religious, Dan at parish priests, and Prof. Roberts at the laity – to analyze.

While the rest of the team played catch-up cleaning their data and analyzing their purchasers, Bianca began to explore what institutions and women religious were purchasing across this period. What quickly became clear is that more than just books were being sold. Medals, beads, pictures, and crucifixes turned out to be popular sellers, a reminder of the importance of material culture to Catholicism. Curious about some of the titles that she repeatedly came across, Bianca looked at the history of three works in particular: Historical Sketches of O’Connell and his Friends, about the great nineteenth-century Irish proponent of Catholic emancipation; An Exposition of the Doctrine of the Catholic Church in Matters of Controversy, by the popular seventeenth-century French orator and polemicist Jacques-Benigne Bossuet; and The Poor Man’s Catechism by John Mannock.

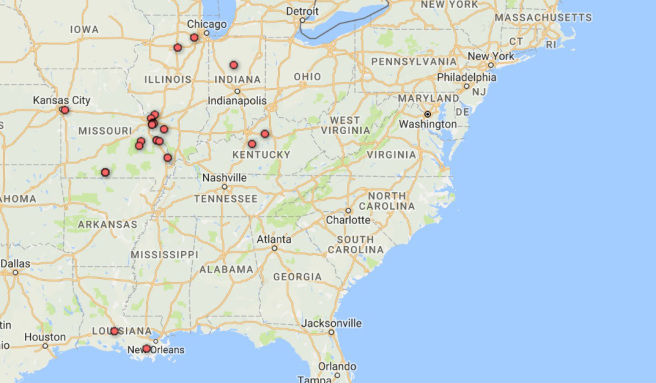

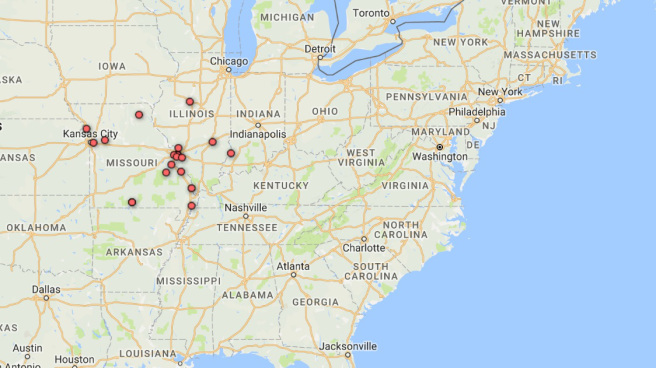

By the mid-point of the semester, the team was ready to start aggregating and visualizing their transcribed and cleaned-up data. A new set of spreadsheets was created listing the names of unique purchasers, their locations at different points in time, and the frequency of their purchases. Most purchasers are only listed in one or two transactions a year. But a handful were very active patrons. Bishop Peter Richard Kenrick (1806-1896), for example, had 34 different transactions in May 1842-April 1843 and another 19 in 1846. Using the functionality of Google Fusion Tables, team members were able to create charts and maps to begin to identify patterns. One seemed to suggest a shift from clergy serving large swaths of scattered rural Catholics across a broad circuit at the start of the decade to their settlement in single parishes by the end. Bianca became particularly interested in thinking about movement and change over the first half of this period. After isolating a list of unique purchasers from 1846 whose location could be ascertained in 1841, she mapped both to see their geographic spread. Even with this limited dataset, her maps reveal the broad expanse of the trade, centered in St. Louis, but stretching east to Kentucky, west to Kansas, north to Chicago and south to New Orleans.

Throughout, the team sought to identify multiple variables about the unique purchasers. This included not only whether they were clergy or laity and their locations at the time of their purchase. The team also researched the order (if any) to which the clergy and women religious belonged. With the exception of the occasional (but inconsistent) “S.J.” after a Jesuit’s listing in the ledger, this information was very rarely recorded. But the Metropolitan Catholic Almanac often does reveal this, so Bianca went to work gathering this information.

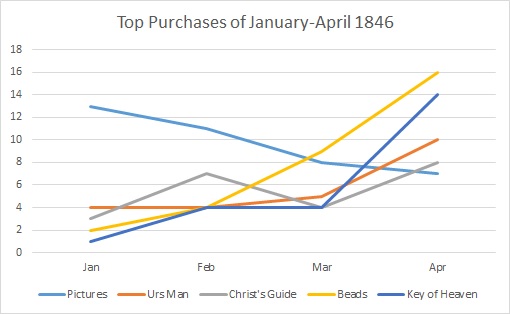

By the end of the semester, all of the team members had a good handle on their purchasers and could begin thinking about the books they bought. Bianca made the greatest progress in the latter inquiry. She resumed the work she had been doing at mid-semester. She used the history of one person’s purchases to craft a preliminary narrative about that consumer in 1846. () Then, in her final post, she undertook an aggregate analysis of sales over the first four months of 1846. Two things jump out from her work. First, the broad range of works being sold. She identified over 348 unique titles, a number that astounded the entire team. Second, she discovered that the best sellers were, less surprisingly, devotional works like Gother’s Sincere Christian’s Guide (22 purchases), The Key of Heaven (23), and the Ursuline Manual (23), but also, more surprising, beads (31) and pictures (39). Charting their purchase over time suggested some seasonal patterns to boot.

In the spring 2017 semester, Bianca is off to study at Loyola’s John Felice Rome Center and is passing the baton to Dan, who will expand his study of the sales of particular books and what their significance might be to Catholics in the antebellum Midwest in a directed study. Stay tuned for more discoveries!

[…] making purchases were and where they were located, we can begin to look at what they were buying. Bianca has done amazing work analyzing the works purchased in 1846, noting that nearly 350 unique items were purchased in that […]