The following post is written by junior Dan Snow, one of this semester’s interns and a 2015-16 Ramonat Scholar. It is the second in a series by the interns about an important ledger that reveals the previously unappreciated role played by Jesuits in supplying the communities of the upper Missouri and Mississippi Valleys with Catholic books in the mid-nineteenth century.

For the past few weeks, I have been looking at the book trade ledger maintained by the Society of Jesus in Missouri from 1842 until 1850. These records detail the book orders of the Jesuits, and show what texts they bought and from whom they purchased them. Hundreds and hundreds of books can be found here, offering information not only on the reading tastes of mid-nineteenth-century Catholics, but also on the Jesuits’ ability to oversee the distribution of these texts within the Western United States. The ledger offers insight on the texts the Jesuits were buying and on the men who sold these books to them. The vendors of these books were primarily American firms and individuals: of the 127 orders between April 1842 and April 1850, just fourteen orders were from European firms. It is interesting to note that while many of the books the Jesuits were buying came from traditional Catholic publishing houses like Sadlier in New York or Benziger in Switzerland, a few of their orders were placed through other clergymen. Only fourteen were made through Catholic priests, yet this reveals an interesting scenario wherein clergymen bought and sold books to other clergymen who then resold these books throughout the country.

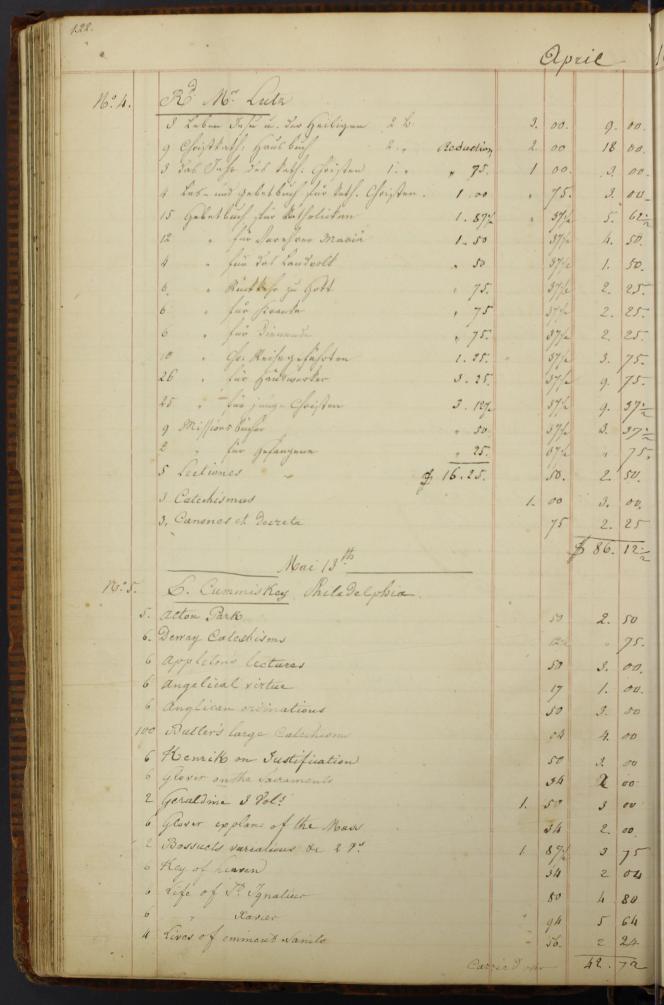

A typical page in the ledger, this specific one showing the order from Fr. Lutz. (Collection of St. Louis University)

Two priests in particular stand out. Fr. Joseph Anthony Lutz (1802-1861) was a German-born priest assigned to the Diocese of St. Louis. In 1828, he performed missionary work near what would become Kansas City, MO and established a small school there. Lutz was then appointed assistant pastor at the Cathedral of St. Louis under Bishop Joseph Rosati. As a secretary for the diocese, Lutz secured books for its parishesas part of his responsibilities: in July of 1834, Fr. Saint Cyr (founder of St. Mary’s, Chicago’s first Catholic parish) wrote to Bishop Rosati asking for him to send Lutz to Chicago with a collection of books that would be of the “greatest utility” in the growing town.

Lutz appears only once within the ledger, but the books that he provided reflect his German heritage. In April 1842, nearly all the books the Jesuits ordered from him were German texts. Most of the works are different variations of prayer books (Gebetbuch): for brides (für Braute), for young Christians (für junge Christen), for prisoners (für Gefangene), etc. Though the quantities are small (the greatest number of copies for any text ordered being 26 copies of a prayer book for craftsmen), it speaks to the needs of a small but steadily growing German presence in Missouri. Hermann, the traditional German center in the state, is located just outside St. Louis. German settlers called this region of Missouri Deutschheim, or ‘German Home’, reflecting the intent of Hermann’s founders who aimed to create a distinctly German town on the American frontier. Through the work of these settlers and a promotional booster work by Gottfried Duden called “Report of a Journey to the Western States of Northern America”, thousands of German immigrants settled in the rural areas around Hermann from 1820 to 1860. From 1830 to 1837 alone, nearly 7,000 German settled in the St. Louis area. It seems likely that the Jesuits’ need for German texts during this time period reflects the growing presence of a sizeable Catholic German community in Missouri.

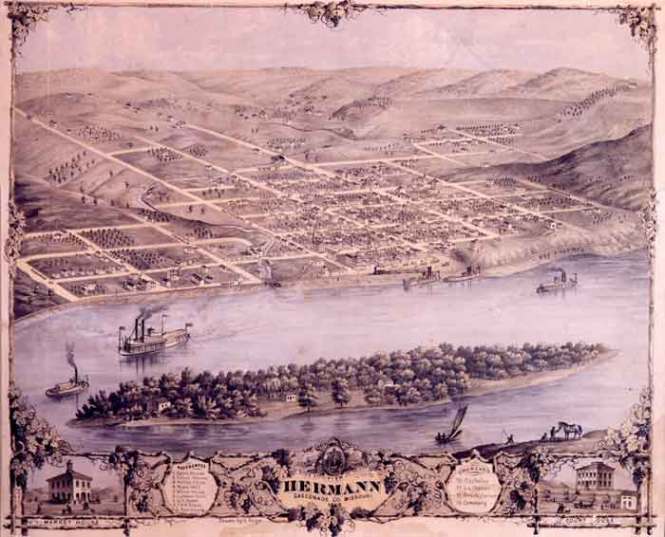

Located on the Missouri River, Hermann was favored by German immigrants for

its similarity to the Rhineland (Image Source: Hermann Area Chamber of Commerce)

The next priest I looked at was Father John Timon (1797-1867). Timon was appointed the first American provincial of the Vincentian Fathers (the Congregation of the Mission) in 1835, and in 1839 was made the prefect apostolic for the newly independent Republic of Texas. In 1841 the Holy See promoted Texas to an apostolic vicariate, and Timon lost his position. The Metropolitan Catholic Almanac and Laity’s Directory lists Timon as Vicar General in the Diocese of St. Louis in 1844, though he likely had held this position for some time prior and was in contact with the Jesuits in the region since at least 1842.

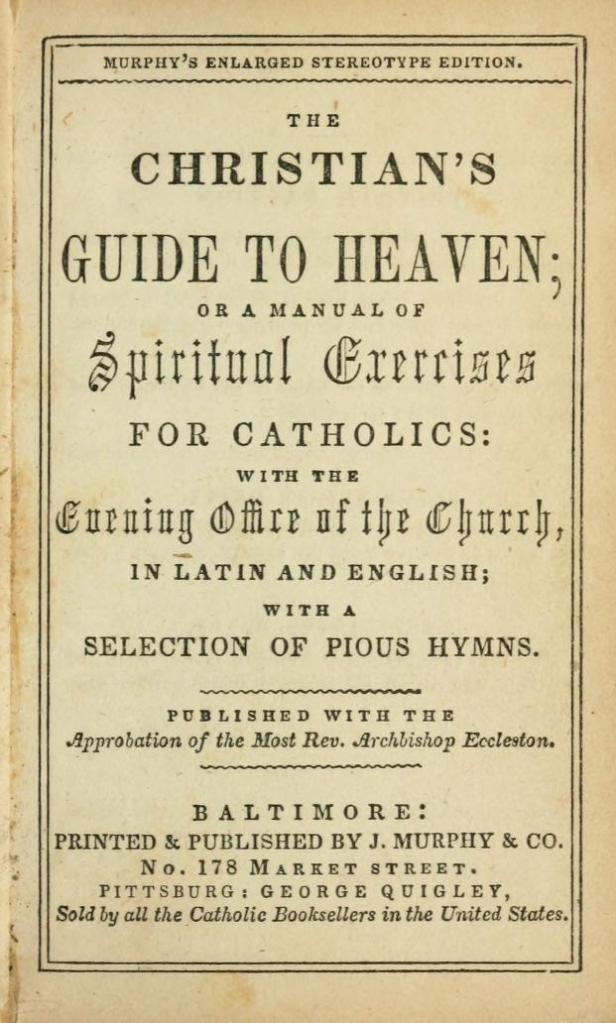

The Jesuits placed five orders with Timon between July 1842 and April 1844. The types of books ordered vary greatly – most are theology works (different Bible editions and translations, prayer books, etc.) but many history and philosophy works appear as well. Also worth noting are the large numbers of French texts (the final order in April of 1844 is particularly French in nature) and German texts that Timon sells. One of the more striking things to note is that two of his best sellers remain consistent across the years: Catechisms and something called the “Christian’s Guide” (likely The Christian’s Guide to Heaven: or, A Manual of Spiritual Exercises for Catholics). In July 1842, Timon sold 2,000 catechisms and 500 guides to the Jesuits, accounting for half the cost of that order. In November he sold 200 more guides, and in April 1844, the Jesuits purchased 1,000 more Catechisms and 100 guides. The significance of these texts lies in their content and volume.

One probable reason why the Jesuits would have needed such a high volume of texts covering the doctrine of the church is education. Looking at an 1844 copy of the Christian’s Guide, it seems as though this text would have been used in the religious education and instruction of those entering into the Catholic faith, or for strengthening the knowledge of already baptized Catholics. I can imagine that these texts would have been bought by the Jesuits and spread across the Midwest to growing parishes and missions, but also used in Catholic schools as textbooks for religious study. In this way, the Missouri Jesuits would have played an important role in the fostering of the Catholic faith in the Western United States. With further research into who the Jesuits were distributing these books to, it would be possible to track Jesuit involvement in Catholic communities and educational institutions.

By focusing on Fr. Lutz and Fr. Timon, and the types of books they were selling, one can gain insight into the operation of the Society of Jesus and into the condition of Catholics in America during this timeframe. With more research, we could gain a greater understanding of the persons involved in this trade and their intentions. It would be interesting to see where Lutz and Timon bought their books. Did Lutz order specialty German books that would have been hard to find in the United States? Did Timon place orders for the Jesuits with publishers they were unfamiliar with? It is also interesting to note that the clergy in the Jesuit ledger only appear during a limited time. The Jesuits first place an order through a priest with Lutz’s order in April 1842, and their last order with a clergyman is with Bishop Francis Kenrick in September 1845. The orders continue for another five years without any being made through a priest. The Jesuits ordered books through priests 14 times during their 50 orders from April 1842 to September 1845. What does it say that so many of these early orders were made through priests, and that no priest sells to the Jesuits from 1846 to 1850? Does this reflect a growing Jesuit relationship with the publishing houses that would have removed the need for a middle-man such as Lutz or Timon? By looking further at the books Lutz and Timon were buying, and who the Jesuits were selling these books to, it should be possible to answer some of these questions and better understand the complex factors at play in the Jesuit ledger.

For more information on Fr. Lutz and/or Fr. Timon, visit the Diocese of Kansas City-St. Joseph and Texas State Historical Association, respectively

[…] ledger, again looking at the vendors that the Missouri Jesuits in the 1840s were buying from. In my last post, I wrote on two priests – Fr. Lutz and Fr. Timon – whose orders comprise less than half of […]